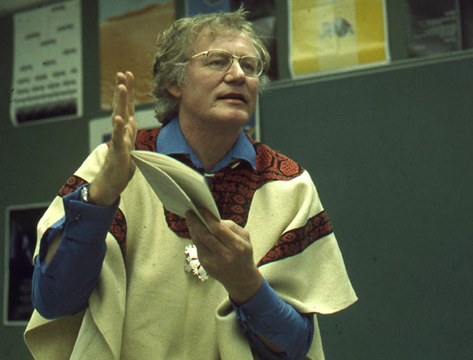

In the second book of this series of posts, we have The Winged Life: The Poetic Voice of Henry David Thoreau, by poet and rogue shaman Robert Bly, published in 1992 (HarperPerennial).

It is especially fitting to discuss this book now since Bly died just last November in his nineties after sadly being afflicted with dementia.

Reading several of Bly’s obituaries, I realized more fully how influential he became as an American poet. And not just a poet. He was famously opposed to the Vietnam War. And after his 1990 book Iron John: A Book About Men (which called, the New York Times obit notes, for “a restoration of primal male audacity”), he was catapulted to cultural prominence.

As Tony Hoagland writes in his 2011 essay about Bly: “From that time on, Bly’s true companions would largely not be other American poets, but cultural thinkers.”

It makes sense that Bly would write this commentary on Thoreau, for he had many of the same values and ways of seeing that moved both Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau. Bly continued the tradition, if we may call it that, of the Transcendentalists, of not needing any intermediary for spiritual insight.

The structure of the book consists primarily of five parts, each one introduced with a commentary by Bly and followed by excerpts from the variety of Thoreau’s writing. (The wonderful woodcuts by Michael McCurdy add greatly to the contemplative tone of the book.)

“Part One – The Bug in the Table” sets the stage for this series of meditations on who Thoreau was as a man, and how he perceived himself and the world around him in those times of the 1840s. How different the world was then! Yet Bly lets us see how relevant much of what concerned the man of Concord still is today.

Transparent Eyeball

As noted in the introductory post, Bly highlights, at the very beginning, these sentences by Thoreau’s friend and mentor, Emerson:

“Standing on the bare ground, – my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space, – all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball.” This book is an exploration of how this kind of experience pervades Thoreau’s life. Nature is the inspiration of his entire outlook.

In Bly’s words now: “Many young men and women want to marry nature for vision, not possession. …The soul truth assures the young man or woman … that in human growth the road of development goes through nature, not around it.”

He excerpts from Thoreau’s Walden the story of “the strange and beautiful bug” which came out from an old table made from apple-tree wood, which had been in a farmer’s kitchen for a lifetime, but its egg must have been deposited in the original tree while it still existed. It was heard gnawing its way out of the table for some time, no doubt awakened by the heat of an urn or other contrivance.

Thoreau says: “Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society… may unexpectedly come forth….”

Bly comments: “This is a marvelous tale…. The story suggests that there is an unhatched abundance inside us that we ourselves have not prepared. Our psyche at birth was not a schoolchild’s slate with nothing written on it, but rather an apple-wood table full of eggs. We receive at birth the residual remains of a billion lives before us.”

In this Part One there are nineteen texts, comprised of poems, Journal passages and excerpts from Walden. This organization is similar in each of the following Parts.

Thoreau was remarkable for his rambles, his long walks in the woods almost every day. As one other selection of his writing from this Part puts it:

“I come to my solitary woodland walk as the homesick go home. I thus dispose of the superfluous and see things as they really are, grand and beautiful. I have told many that I walk every day about half the daylight, but I think they do not believe it. … It is as if I always met in those places some grand, serene, immortal, infinitely encouraging, though invisible, companion, and walked with him.”

So As Not to Live Meanly

Part Two is called “The Habit of Living Meanly.” In Bly’s commentary, he notes that Thoreau observed how many of the people around him took on that habit. Living meanly to Thoreau meant living without sincerity, living to other’s standards, living like a kind of human ant occupied with small burdens. “The ancient metaphor for living meanly is sleep,” Bly says.

Thoreau sought a deeper life, which to every person must be at least partially different. Bly remembers that the first sentence of Thoreau’s that he ever memorized was:

“Moreover, I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives; some such account as he would send to his kindred from a distant land; for if he has lived sincerely, it must have been in a distant land to me.”

Thoreau feels grief for the life wasted about him. In that famous quote from Walden given here:

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats.”

Part Three is entitled “Going the Long Way Round.” As Bly says, Thoreau’s major life decision was his resolution to live what he understood to be a sincere life. “Thoreau wanted greatness, and he wanted to live greatly, but most of all he wanted not to live meanly.”

The Importance of Moratoriums

The young Thoreau insisted on taking a moratorium, a pause in the designs of the world upon him. Bly says, “I feel that Thoreau’s declaration of the need for a moratorium is his greatest gift to the young.”

In Thoreau’s case his moratorium, in the years before he published Walden, may have gone on too long. He resigned himself to not being at home in either male or female company.

Thoreau wrote in his journal: “By my intimacy with nature I find myself withdrawn from man. My interest in the sun and the moon, in the morning and the evening, compels me to solitude.”

His pursuit of solitude is further illustrated by one of his Journal entries: “By poverty, i.e. simplicity of life and fewness of incidents, I am solidified and crystallized, as a vapor or liquid by cold. It is a singular concentration of strength and energy and flavor.”

In Part Four, “Seeing What is Before Us,” Bly momentarily revisits Emerson for his description of what it was like to walk with Thoreau: “It was a pleasure and a privilege to walk with him. He knew the country like a fox or a bird, and passed through it by paths of his own.” Emerson recounts how detailed and patient Thoreau was in his observations of nature, taking with him an old book to flatten flowers in, a diary and pencil, a spy-glass for birds, a hand-held microscope, a jackknife and twine. Thoreau knew to the day when each type of wildflower would bloom.

Faculties of the Soul

Thoreau read widely, everything from Eastern spiritual books to Goethe and Schelling. These perspectives informed his detailed descriptions of the nature around him. He seemed to take to heart Coleridge’s advice that “each object rightly seen unlocks a new faculty of the Soul.” Thoreau asserted in his Journal, against our separation from nature, that “I am made to love the pond and the meadow….”

At the end of this section, after a brief discussion of Thoreau’s ability to also know darkness, Bly writes: “We feel in Thoreau’s life the presence of a fierce and long-lived discipline, and one reward of that discipline was his grasp of the wildness in nature.”

In the final Part Five, “In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World,” Bly notes that Thoreau was certain that the civilizations of Greece, Rome and England have been sustained by the primitive forests that surround them, and “that these same nations have died and will end when the forests end.”

Bly suggests that Thoreau was one of the first writers in America to accept the ancient idea that nature is not a fallen world, but instead a veil for the divine world.

Refreshed by Nature

In Thoreau’s words:

“We can never have enough of nature. We must be refreshed by the sight of inexhaustible vigor, vast and titanic features, the sea-coast with its wrecks, the wilderness with its living and its decaying trees, the thunder-cloud, and the rain which lasts three weeks and produces freshets. We need to witness our own limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.”

Bly concludes his book with an insightful brief biography of Thoreau, who died in his forty-fourth year of tuberculosis.

Bly does a good job of presenting the man to us. Thoreau had his greatness, and his limitations — there is much more depth in Bly’s examination then I am able to touch on here. But what might we take from all this?

It would be wise, I think, for us as writers, and as human beings, to take long walks in wild places. And pay attention to what we see and feel. There is no good substitute.

[Home]

Notes

This is the second book considered in this series of posts after:

Three Books for the Writer Self – Introduction

Three Books for the Writer Self – 1) The Soul’s Code

For my own encounters with Thoreau and Emerson, there are the posts A Walk With Hank, and Chant the Beauty of the Good.

Miller set up a company with her husband to publish these books in Winnetka, Illinois and the first one, In The Nursery, was issued in 1920. The first six-volume sets were often, as a promotion, enclosed in a small wooden house. The six were eventually split into 12 thinner books for the benefit of small hands. An interesting aspect of her publishing company was its staffing predominantly by women, including the sales force. This was most unusual at a time when women were deemed best suited to staying at home.

Miller set up a company with her husband to publish these books in Winnetka, Illinois and the first one, In The Nursery, was issued in 1920. The first six-volume sets were often, as a promotion, enclosed in a small wooden house. The six were eventually split into 12 thinner books for the benefit of small hands. An interesting aspect of her publishing company was its staffing predominantly by women, including the sales force. This was most unusual at a time when women were deemed best suited to staying at home. Volume 8, Flying Sails, featured for me “Gulliver’s Travels to Lilliput” adapted from Jonathan Swift. The accompanying illustrations are marvelous, of Gulliver tied down by many tiny figures. This volume also included a couple of stories from the Arabian Nights, “The Adventures of General Tom Thumb,” and Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

Volume 8, Flying Sails, featured for me “Gulliver’s Travels to Lilliput” adapted from Jonathan Swift. The accompanying illustrations are marvelous, of Gulliver tied down by many tiny figures. This volume also included a couple of stories from the Arabian Nights, “The Adventures of General Tom Thumb,” and Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.” In this last, retold from the Chanson de Roland, Roland heroically blows his horn, Oliphant, at the end of a great battle to call for relief for his men and himself, only to finally die.

In this last, retold from the Chanson de Roland, Roland heroically blows his horn, Oliphant, at the end of a great battle to call for relief for his men and himself, only to finally die.

Recent Comments