Often the internet seems like a collection of lists: the 100 best pop-songs, the 15 worst scams, and all the rest. People seem to respond to numbered compilations.

In the science-fiction realm, I’ve read quite a few lists about some aspect of “best”, whether of this year, or by women authors, or the most technologically significant.

In the end, they are all personal lists – usually one person’s idea and often displaying whatever social correctness we are supposed to elevate.

This is my list, based on an admittedly incomplete sampling, although over quite a few decades. Many of them were written in the 1950s through 1960s, which to me is the bedrock of modern science-fiction. You can’t really understand where science-fiction is today without recognizing the immense talent that preceded the current flowering of the genre and its many brilliant authors.

If you were to read the novels mentioned here, I feel you could only come away with a deep appreciation for the wonder and otherness that science-fiction seeks to portray.

Such is the depth of the field that many variations of this list are possible. This particular one though has stories that touched me on many different levels, and I think still could for anyone who reads them anew.

As I went through these titles, I was struck hard again by the sweep of imagination of the authors. The daring.

A few of the entries below are trilogies or series, but in my mind those are one big novel.

I will go through them chronologically.

1. Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

I was hard-pressed whether to select this dystopian novel, published in 1932, or George Orwell’s later take on the same theme, 1984. I read them both in a log cabin in northern British Columbia in the 1960s as an impressionable boy. They served to make me deeply suspicious of all forms of authority.

In the end, Huxley’s novel is the more menacing of the two. While 1984 portrays overwhelming brutality against the individual by the state, in Brave New World people are effectively seduced to accept their utter servitude. As Huxley stated in a letter to Orwell:

In the end, Huxley’s novel is the more menacing of the two. While 1984 portrays overwhelming brutality against the individual by the state, in Brave New World people are effectively seduced to accept their utter servitude. As Huxley stated in a letter to Orwell:

“Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience.”

2. Foundation Trilogy, Isaac Asimov

Set against a backdrop of galactic empire, the psychohistorian Hari Seldon founds a secretive branch of mathematical sociology. It enables him to predict the future of large populations, and through it, he predicts the fall of the empire. He foresees a new Dark Age lasting 30,000 years, but through his new discipline, he endeavours to slightly deflect for the better the onrushing series of events. In later millennia he appears as a kind of hologram, although long dead, to help guide what happens, due to his calculations.

A quote from Hari Seldon that has stuck with me: “Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent.”

I still remember holding the hard-back volumes of this intriguing story by Isaac Asimov which began with the trilogy from 1951 onward, eventually extending to more volumes in the 1980s. I read it several times during my teenage years. Hari Seldon was an amazing character to me. Foundation won the one-time Hugo Award for “Best All-Time Series” in 1966.

I still remember holding the hard-back volumes of this intriguing story by Isaac Asimov which began with the trilogy from 1951 onward, eventually extending to more volumes in the 1980s. I read it several times during my teenage years. Hari Seldon was an amazing character to me. Foundation won the one-time Hugo Award for “Best All-Time Series” in 1966.

Of course Isaac Asimov was one of the most famous of science-fiction writers, with work ranging from the I, Robot series to the novel The Caves of Steel.

3. Childhood’s End, Arthur C. Clarke

The human race is about to enter a new phase. At the end of this poignant story, published in 1953, we come to understand that children are undergoing a transformation. They are metamorphosing into something that transcends human existence. The facilitators of this change are a tragic alien race who peacefully invaded Earth.

The aliens are only caretakers of the human race while it undergoes the transformation into something spiritually superior. What has been the human race will be no more.

The aliens are only caretakers of the human race while it undergoes the transformation into something spiritually superior. What has been the human race will be no more.

The English author, Arthur C. Clarke was a writer, futurist and inventor who also wrote the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey and many other novels such as Rendezvous with Rama. He was a well-known proponent of space travel.

I remember him also for short stories such as The Nine Billion Names of God, where Tibetan monks strive to encode all the possible names of God. They believe the universe was created for this purpose. They need modern technology to complete their task, and enlist the expertise of two Westerners. As the monks complete their long mission, “overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.”

4. More Than Human, Theodore Sturgeon

A novel about six misfits, each with a strange power, who come together after many tribulations to form a new kind of human being, homo gestalt, a whole of combined consciousness.

The story, published in 1953, was praised by some reviewers for “its crystal-clear prose, its intense human warmth and its depth of psychological probing.”

The story, published in 1953, was praised by some reviewers for “its crystal-clear prose, its intense human warmth and its depth of psychological probing.”

Others said the novel “transcends its own terms and becomes Sturgeon’s greatest statement of one of his obsessive themes, loneliness and how to cure it.”

Sturgeon also coined “Sturgeons Law”: “Ninety percent of science fiction is crud, but then, ninety percent of everything is crud.”

5. The Kraken Wakes, John Wyndham

Another novel from 1953, this apocalyptic story begins with a journalist and his wife observing the fall of mysterious objects into the ocean.

The story has three sections: the first where the aliens arrive and do mysterious underwater things, the second when the aliens attack in “sea tanks” that send out sticky tentacles and drag people into the water, and the third where the aliens raise the sea level and change the climate, and civilization collapses. This all takes place over many years.

A professorial third character with considerable insight tries to warn everyone about what may happen, but is widely ignored due to his alienating manner.

Even by the end of the novel, nobody ever sees the aliens.

Reviewers praised the novel as “a solid and admirable story of small-scale human reactions to vast terror.”

John Wyndham, a British author, also wrote The Day of the Triffids, The Midwich Cuckoos and The Chrysalids, among other notable works.

6. A Canticle for Liebowitz, Walter M. Miller, Jr.

Published in 1959 and winning the Hugo Award for best science-fiction novel in 1961, this story covers a post-apocalyptic period of thousands of years. The apocalypse was occasioned by nuclear holocaust.

In the 26th century, Brother Francis Gerard of the Albertian Order of Leibowitz of the Catholic Church is on a vigil in the Utah desert. Brother Francis discovers the entrance to an ancient fallout shelter containing “relics”, such as a 20th-century shopping list which becomes sanctified as a holy remnant of an ancient world. The Church persists as the preserver of civilization.

The novel has been subject to considerable literary and critical analysis. In other words, it came to be treated with respect outside the science-fiction genre.

The novel is structured in three parts separated by six hundred years. This book was my first exposure to any model of cultural history. In Miller’s own words from another work: “All societies go through three phases…. First there is the struggle to integrate in a hostile environment. Then, after integration, comes an explosive expansion of the culture-conquest…. Then a withering of the mother culture, and the rebellious rise of young cultures.”

In the end, this cyclical process catches up, in a tragic way, to all that humanity hopes to accomplish.

7. The High Crusade, Poul Anderson

When an extraterrestrial scout ship lands in medieval England, it is encountered by a knight recruiting a force to help Edward III in the Hundred Years War against France. It seems the aliens have forgotten how to do hand-to-hand combat, and Sir Roger and his men capture the ship.

The whole set-up still makes me grin. Sir Roger and company think the ship is a French trick. The local villagers finish off the rest of the alien force, except for one, and join the soldiers in the ship. Sir Roger determines to go to France to win the war and then liberate the Holy Land.

With the grudging aid of the last alien, representing a tyrannical empire bent on invading Earth, they take off. The alien misleads the Englishmen and the ship actually heads off towards another of the alien empire’s worlds. Adventures ensue.

The prolific Poul Anderson was one of the great science fiction authors. His books were nominated for seven Hugo and three Nebula awards. The High Crusade was published in 1960. Anderson also wrote such novels as There Will Be Time (1972) and The Boat of A Million Years (1989).

8. Dark Universe, Daniel Galouye

Another post-nuclear-apocalypse novel, Dark Universe from 1961 finds survivors retreated underground, where they live in total darkness.

Since the survivors have no visual ideas of Light and Darkness, the concepts become religious. They believe that the Light Almighty banished humankind from Paradise during a conflict with the demon, Radiation, and his two lieutenants, Cobalt and Strontium.

Since the survivors have no visual ideas of Light and Darkness, the concepts become religious. They believe that the Light Almighty banished humankind from Paradise during a conflict with the demon, Radiation, and his two lieutenants, Cobalt and Strontium.

Jared is the son of the leader of the survivors who use click-stones and echoes to navigate the darkness. Jared goes on a quest for Darkness and Light and encounters another clan of survivors who use infrared to get around.

Galouye creates an ingenious world, which in the end is redeemed by the Light. Many have noted the resemblance of the story to Plato’s allegory of the cave.

The novel was nominated for a Hugo in 1962, but lost out to the next novel in this list.

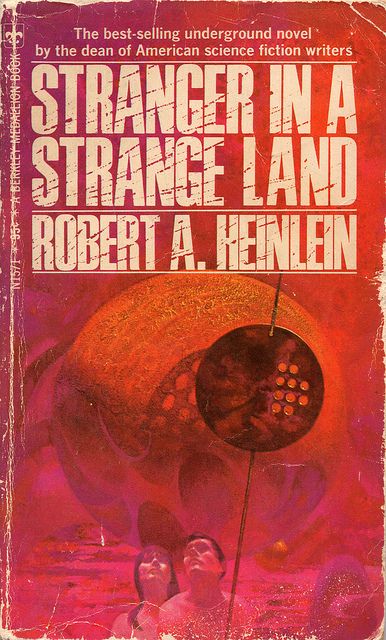

9. Stranger in A Strange Land, Robert Heinlein

This is the story of Michael Valentine Smith, born on Mars and raised by Martians, who comes to Earth and encounters the United States after World War III, where religions are powerful.

He becomes a celebrity and his presence begins to transform human society. He exhibits psychic abilities and superhuman intelligence, while having a kind of open-minded innocence.

However, his appearance and actions on Earth shake the political and cultural balance and his life becomes in danger.

According to Wikipedia, Heinlein named his main character “Smith” because of a speech he made at a science fiction convention regarding the unpronounceable names assigned to extraterrestrials.

He also was to write about the novel, “I was not giving answers. I was trying to shake the reader loose from some preconceptions and induce him to think for himself, along new and fresh lines.”

It became the first science-fiction novel to enter The New York Times Book Review‘s best-seller list.

During the 1960s, the book became a countercultural favorite, not least for the word “grok” which took on the meaning of a coming together of subject and object that can’t always be articulated. When you grok something, you not only understand it, you become, in some sense, a part of it, and it, a part of you.

10. The Immortals, James Gunn

Published in 1962 and incorporating several previously published stories, this is the chronicle of a small group of immortals surviving on the edge of a dystopian society which is striving to hunt them down.

They are living fountains-of-youth, due to a genetic mutation, whose blood can make others immortal too (if replenished every month).

As one reviewer on Goodreads notes: “…The Immortals opens with scenes that could almost come from a crime novel rather than a science fiction story. Private detectives are hired, people are on the run, evil rich men will do anything to get what they want, no one can be trusted.”

I remember it for its thriller-like excitement and the tense pacing of its writing.

James Gunn, who only recently died in 2020, was a well-known professor of English and promoter of science-fiction as a humanistic endeavour at the University of Kansas.

11. Cities In Flight series, James Blish

This four book series was published from 1950 to 1962, but the one that sticks with me most was A Life For the Stars from 1962.

The premise is that entire cities from Earth fly among the stars using an anti-gravity device called the Dillon-Wagoner Graviton Polarity Generator, or spindizzy for short.

The spindizzy allowed some cities to escape the oppression of a tyrannical regime on Earth and look for work among the other denizens of the galaxy.

The 1962 book describes the rise of 16-year-old Chris Deford who eventually becomes the city manager of New York City as it wanders through the cosmos.

These are stories for which the term “space opera” was invented.

The American writer James Blish also wrote a series of Star Trek novelizations and the Hugo Award winning A Case of Conscience in 1959.

12. Way Station, by Clifford D. Simak

As a lonely teenager, there was something about this story of a young man managing a way station for time travelers that resonated with me. The young man, Enoch, stays the same age while those in the normal world around him get older, and this gets difficult to explain after a while. Originally he is a Civil War veteran.

Eventually after a hundred years or so, the US Government takes an interest and a CIA agent is sent to investigate him. This is the beginning of many adventures.

Published in 1963, the book went on to win the 1964 Hugo Award for best novel.

Clifford Simak had an unique, warm style of writing.

He once stated:

“Overall, I have written in a quiet manner; there is little violence in my work. My focus has been on people, not on events. More often than not I have struck a hopeful note… I have, on occasions, tried to speak out for decency and compassion, for understanding, not only in the human, but in the cosmic sense. I have tried at times to place humans in perspective against the vastness of universal time and space. I have been concerned where we, as a race, may be going, and what may be our purpose in the universal scheme….”

In 2019, Netflix announced plans, so far unfulfilled, to make a movie based on the book.

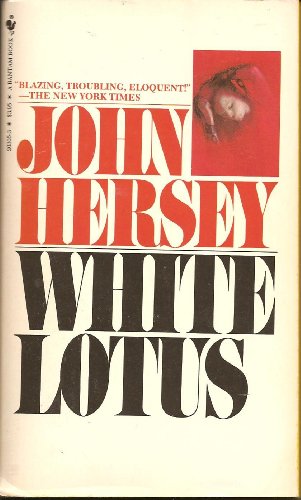

13. White Lotus, John Hersey

Here is a writer from the literary mainstream who created one of the best alternative history novels that I’ve come across. Some might call it speculative fiction, or other terms to make it more respectable, but it is still science-fiction to me.

In this 1965 novel, white Americans have become enslaved by the Chinese and are now a subservient race. The story follows a young Arizona girl renamed White Lotus.

In the memorable prologue of the story, White Lotus raises one knee and stands on the other foot to take the posture of a sleeping bird, in an effort to shame the Chinese governor as a non-violent protest against tyrannical treatment.

Her simple act of standing before her captors on one leg, head bowed like a sleeping bird becomes an often repeated act of nonviolent civil disobedience, an unconventional act in the spirit of Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King.

John Hersey was born in China, the son of Protestant missionaries, and learned to speak Chinese before he learned English.

As a journalist, his account of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, celebrated for its thoughtful and horrified humanity, was judged the finest piece of journalism of the 20th Century by a 36-person panel associated with New York University.

Hersey’s first novel, A Bell for Adano, about the Allied occupation of a Sicilian town during World War II, won the Pulitzer Prize for the novel in 1945.

14. Ubik, Phillip K. Dick

Phillip Dick was a strange and volatile man. He is now celebrated for the movie adaptations of such writings as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Blade Runner) and The Minority Report (Minority Report).

He had a hallucinogenic view of reality fed in part by actual hallucinogens.

But as Wikipedia points out:

“His fiction explored varied philosophical and social questions such as the nature of reality, perception, human nature, and identity, and commonly featured characters struggling against elements such as alternate realities, illusory environments, monopolistic corporations, drug abuse, authoritarian governments, and altered states of consciousness.”

His 1969 novel Ubik illustrates much of this. In it psychic powers are used by corporations for business espionage, and cryonic technology preserves recently deceased people in hibernation.

It follows Joe Chip, a technician at a psychic agency who, after an assassination attempt, begins to experience strange alterations in reality that can be temporarily reversed by a mysterious store-bought substance called Ubik.

15. The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula Le Guin

In this 1971 novel, a man wakes up one morning and discovers that his dreams have the ability to alter reality.

From this simple and imaginative premise, Le Guin devises a tale about a man who goes to a psychiatrist about his problem. The psychiatrist understands immediately the power his patient wields.

At one point the protagonist dreams of aliens who become a reality.

The patient finally understands that he must preserve reality itself as the psychiatrist becomes adept at manipulating the man’s dreams for his own purposes.

Of course Le Guin is famous for many of her thoughtful, culturally significant novels, including The Dispossessed, The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea trilogy. She also wrote much non-fiction, including essays about her craft, which I found quite inspiring (Steering the Craft: A 21st-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story).

16. The Sheep Look Up, John Brunner

This novel from 1972 is the third in what has been called British author Brunner’s near future “Club of Rome Quartet.” The Sheep Look Up concerned itself with consumerism and rampant pollution. Stand On Zanzibar was about overpopulation, The Jagged Orbit concerned itself with racial tension and violence, and the later The Shockwave Rider dealt with technology and future shock.

As much as I admire these books and Brunner, they often now seem outdated, surpassed by actual events. But his prescience in many cases was spot-on. In Shockwave Rider from 1975, for instance, he created a computer hacker hero before anyone even heard of such a thing.

In The Sheep Look Up, water pollution is so severe that “don’t drink” notices are frequently issued. Household water filters are popular items. Air pollution has reached the point that people in urban areas can’t go outside without wearing masks. The fumes left behind by aircraft are such that it causes air sickness in planes trailing behind. California is blanketed by a thick layer of smog that prevents the sun from shining through. Acid rain forces people to cover themselves in plastic so that their clothes don’t get ruined. The sea has become so polluted and the beaches so strewn with garbage, that people now vacation in the mountains. (Not so far-fetched, no?)

It follows several characters over the course of a year as their paths intertwine while they struggle to cope with the drastic changes in the environment, and as the United States starts to collapse under the weight of pollution. It is a pessimistic novel redeemed for me by its somewhat experimental structure, and the density of its ideas and insights about our world’s problems.

17. Lord Valentine’s Castle, Robert Silverberg

Robert Silverberg is one of my favorite science-fiction authors for the excellence of his writing, the philosophical cast of his mind, and his tendency towards themes of transcendence.

He is more celebrated for earlier novels such as A Time of Changes, The World Inside, and Downward to the Earth, deservedly so, but for some reason this novel sticks with me more.

Lord Valentine’s Castle (1980), part of what is known as the Majipoor Series, incorporates aliens, galactic empire, descendants of colonists, lords, castles and wizards to become that odd genre creature, science fantasy.

The story takes place on the gigantic planet Majipoor. It is about ten times the size of Earth, with cities often housing as many as 10-20 billion citizens. We follow a young man named Valentine who suffers from amnesia and who joins a troupe of jugglers during celebrations for the ascension of a new Coronal, the emperor of this planet, also named Valentine (which is said to be a very common name).

Gradually, we learn that the juggling Valentine has been robbed of most of his memories, and has had his true body stolen from him. He is the rightful Coronal of Majipoor.

The planet of Majipoor becomes another character in the narrative. It is full of people, creatures, machines, alien races and interesting locations.

This straightforward, in many ways, adventure story exhibits Silverberg’s wonderful writing craftsmanship.

18. Plague Year Trilogy, Jeff Carlson

Microscopic machines designed to fight cancer instead go awry and begin to disassemble warm-blooded tissue to make more of themselves. Eventually the human body succumbs to the onslaught of the spore-like machines. They spread like a virus by way of bodily fluids and through the air.

Either on purpose or as a design flaw, the nanovirus is limited by altitude, namely 10,000 feet. All warm-blooded animals are killed below that elevation, while humanity retreats to high places.

With thriller-like pacing, the Plague Year trilogy (begun in 2007) portrays humanity in extremis with two key characters struggling to survive and turn the tide. Over the three volumes, with Plague War in 2008, and Plague Zone in 2009, we are taken on a remarkable adventure. Cam, a ski bum with full emergency medical training and an impressive talent for survival, and Ruth, a genius capable of manipulating and designing nanotech together fight to save the world.

In 2008, Plague War was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award.

Sadly, Jeff Carlson died in 2017 of cancer at only 48 years old.

19. The Passage Trilogy, Justin Cronin

Justin Cronin, another author from the literary mainstream, wrote The Passage, 2010, The Twelve, 2012, and The City of Mirrors, 2016, after his daughter asked him to write a book about a “girl who saves the world.”

These are books slightly hard to define in that they straddle the intersection of the science-fiction, horror and fantasy genres. Some blithely describe them as novels about vampires, which are a major element, but this categorization does an injustice to the depth of the writing, characterizations and story.

I was swept away by the quality of the writing. One reviewer said of the trilogy, “There is a sense as you read this series that you are witnessing the creation of a modern classic.”

Colonies of humans attempt to live in a world filled with superhuman creatures who are continually on the hunt for fresh blood. It all starts when an abandoned young girl named Amy becomes an unwitting test subject in an attempt to use an ancient Bolivian virus to create a perfect super soldier. The virus may be the source of the vampire myth. That young girl goes on after many harrowing adventures to eventually fulfill Cronin’s daughter’s wish.

The reviewer quoted above also writes: “The scope of the trilogy is staggering at times. We see characters grow from scared kids to brave heroes, going on to become parents, then grandparents, then legends.”

20. The Nexus Trilogy, Ramez Naam

This trilogy has been described as a “postcyberpunk thriller”. The three volumes, Nexus, Crux, and Apex were written by their American author (born in Egypt) from 2012-15.

Set in 2040, the hero Kaden Lane is a scientist who works on an experimental nano-drug, Nexus, which allows the brain to be programmed and networked, connecting human minds together. As he pursues his work, governments and corporations take an interest and begin to threaten.

Near the beginning of the trilogy genetically enhanced supersoldiers become vegetarians and pacifists after being dosed with Nexus and realizing first-hand the suffering caused by their actions. At the same time, sociopaths dose with Nexus so they can feel the pain they inflict on others.

At the climax of the final book a distributed intelligence made up of thousands of Nexus-linked humans tries to save the world by healing a posthuman AI goddess who was tortured into madness by her near-sighted human captors.

I was enthralled by the books. The pacing and events are definitely that of a thriller, while the wild possibilities of computer-brain interfaces, and linked human consciousness, are explored in depth.

In Conclusion

This was a sentimental journey back to considering many of these novels, although their worth is much more, I would argue, than pure nostalgia.

I did realize one insight as a result of doing this. The force of thinking and feeling realized in Emerson’s and Thoreau’s transcendentalism, that quest for the true and transcendent in our lives, has gone largely dormant in our culture. But I believe that in not a few of the science-fiction novels noted here, that quest reappears to evocatively light up the minds of talented writers. It has been expressed through narratives which include aliens and galactic empires, and stories about dreams and reality and the nature of consciousness.

It is amusing to reflect on the possibility that the best of Emerson and Thoreau lives on through science-fiction.

[Home]

Despite all the attention paid to AI, synthetic biology is a technological revolution going on in parallel with it and with

Despite all the attention paid to AI, synthetic biology is a technological revolution going on in parallel with it and with  For instance last year a drug-developing AI invented 40,000 potentially lethal molecules in six hours. Researchers put AI normally used to search for helpful drugs into a kind of “bad actor” mode to show how easily it could be abused at a biological arms control conference.

For instance last year a drug-developing AI invented 40,000 potentially lethal molecules in six hours. Researchers put AI normally used to search for helpful drugs into a kind of “bad actor” mode to show how easily it could be abused at a biological arms control conference. In the end, Huxley’s novel is the more menacing of the two. While 1984 portrays overwhelming brutality against the individual by the state, in Brave New World people are effectively seduced to accept their utter servitude. As Huxley stated in a letter to Orwell:

In the end, Huxley’s novel is the more menacing of the two. While 1984 portrays overwhelming brutality against the individual by the state, in Brave New World people are effectively seduced to accept their utter servitude. As Huxley stated in a letter to Orwell: I still remember holding the hard-back volumes of this intriguing story by Isaac Asimov which began with the trilogy from 1951 onward, eventually extending to more volumes in the 1980s. I read it several times during my teenage years. Hari Seldon was an amazing character to me. Foundation won the one-time

I still remember holding the hard-back volumes of this intriguing story by Isaac Asimov which began with the trilogy from 1951 onward, eventually extending to more volumes in the 1980s. I read it several times during my teenage years. Hari Seldon was an amazing character to me. Foundation won the one-time  The aliens are only caretakers of the human race while it undergoes the transformation into something spiritually superior. What has been the human race will be no more.

The aliens are only caretakers of the human race while it undergoes the transformation into something spiritually superior. What has been the human race will be no more. The story, published in 1953, was praised by some reviewers for “its crystal-clear prose, its intense human warmth and its depth of psychological probing.”

The story, published in 1953, was praised by some reviewers for “its crystal-clear prose, its intense human warmth and its depth of psychological probing.”

Since the survivors have no visual ideas of Light and Darkness, the concepts become religious. They believe that the Light Almighty banished humankind from Paradise during a conflict with the demon, Radiation, and his two lieutenants, Cobalt and Strontium.

Since the survivors have no visual ideas of Light and Darkness, the concepts become religious. They believe that the Light Almighty banished humankind from Paradise during a conflict with the demon, Radiation, and his two lieutenants, Cobalt and Strontium.

Recent Comments