Write Like Hemingway — A Book Review

Write Like Hemingway: Writing Lessons You Can Learn From the Master

— R. Andrew Wilson. Adams Media, 2009

____________________________________

I’ve always had a hankering to write more like somebody else rather than how I usually write.

And not to be too sardonic, I have admired Ernest Hemingway’s writing style, the relatively little I know of it; I’ve especially appreciated the inspiration of his “one true sentence” to get started with a piece of writing (see Currents of the River).

There are things to learn from this book, and also aspects of it that annoyed me greatly.

The author is an academic who has written about other American writers such as Melville and Henry James. In his preface he says:

“The idea of this book is to learn what we can about writing from Ernest Hemingway, the man who did more than any other American author to change the face of the English written word. He also changed the way we use literature to see the world that we inhabit.”

He counsels the reader to have Hemingway’s Complete Short Stories at hand. I decided I needed to read at least a little more of Hemingway’s writing before I started so I went out, purchased and read The Snows of Kilimanjaro And Other Stories, which has many but not all of his best known stories.

I read some of Hemingway when I was in university but that was about it for formal study. It was interesting to read the short story collection, with quite a few of its stories brand new to me. The main impression I came away with, despite all the style, was one of how dismal the world looks through Hemingway’s eyes.

I read some of Hemingway when I was in university but that was about it for formal study. It was interesting to read the short story collection, with quite a few of its stories brand new to me. The main impression I came away with, despite all the style, was one of how dismal the world looks through Hemingway’s eyes.

The dismal human condition

Now I realize that the human condition often is dismal, but Hemingway seemed to have an affinity for that mood. Coupled with the casual brutality, both physical and emotional, that he captures so well, I was left aware of his artistry while thinking that this is a drinker’s view of the world.

(Susan Beegle in an article on Hemingway says he was “a thinly controlled alcoholic throughout much of his life.”)

This is also indicated I think by Hemingway’s overbearing and sentimental affectation of having everyone call him “Papa.” The author Wilson compounds this annoyance by referring to him constantly as Papa. He’s not my damn father….

Now that I’ve gotten that peeve out of the way, what are the main features of Hemingway’s writing that we might want to emulate?

Hemingway started his writing career as a newspaperman. And he took that terse “just the facts” approach and deepened it enough to eventually earn the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Wilson begins his examination of Hemingway’s style by summarizing its main points, a few of which are:

— write objectively, describing details of the world, not emotions

— emphasize nouns

— choose active verbs, not passive

— use common vocabulary

— depend upon dialogue to draw characters

— use repetition to remind readers what they’ve read

It’s a stony style of writing. There’s not a lot of hoopla in it.

There is a lot of the standard “how to write” advice in this book, which if you read enough of them becomes trite and banal. “Show don’t tell,” “write about what you know,” and the rest of it. But with his description of the Iceberg Theory as Hemingway applied it, the book starts to better live up to its name.

Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory

The Iceberg Theory is about understatement and the art of what to leave out. Wilson summarizes it in four principles:

1. Write about what you know but don’t write all that you know.

2. Grace comes from understatement.

3. Create feelings from the fewest possible details

4. Forget the flamboyant

Each scene in a story, Wilson notes, should suggest more tension than it states.

Wilson also emphasizes the fabled short, declarative nature of Hemingway’s writing. But it misrepresents Hemingway’s style, I think, to focus too much on short sentences. Reading the short story collection, I was surprised to find how meandering his sentences could be. For instance:

Wilson also emphasizes the fabled short, declarative nature of Hemingway’s writing. But it misrepresents Hemingway’s style, I think, to focus too much on short sentences. Reading the short story collection, I was surprised to find how meandering his sentences could be. For instance:

“I took the young Irish setter for a little walk up the road and along a frozen creek, but it was difficult to stand or walk on the glassy surface and the red dog slipped and slithered and I fell twice, hard, once dropping my gun and having it slide away over the ice.” (From the story A Day’s Wait.) Or,

“The three with medals were like hunting-hawks; and I was not a hawk, although I might seem a hawk to those who had never hunted; they, the three, knew better and so we drifted apart.” (From the story In Another Country.)

But it’s true, if all his sentences were short, knobby, declarative ones, his writing would lack the variety and nuance it actually contains.

On a side note, it is striking how he uses the word “and” to link moments together.

What about Hemingway’s techniques for characterization?

He tended to model his fictional people, Wilson says, after people he knew, although Hemingway insisted their final form was entirely imaginative. In the end they were probably composites of at least several different people.

Hemingway focused a lot on the difference between flat and round characters. A round character cannot be summed up in one sentence. He or she has a lot of the “iceberg” about them. Round characters also tend to be dynamic. They can change over time because of what happens to them and what they do themselves.

Effective dialogue

Hemingway’s skill with dialogue is ultimately mysterious in how he is able to convey so much about his characters through just what they say, and don’t. Again, his dialogue suggests more than it reveals. Wilson says:

“With Hemingway, dialogue often appears with less ink on the page than the white space around it. Its nakedness suggests both character and scene.”

Effective dialogue cuts out the inessential. Or as sage advice from some forgotten writing book put it: Dialogue is what characters do to each other.

In some ways, the commonness of some of the writerly advice in this book just attests to the influence Hemingway’s style has come to have. The advice to keep your dialogue tags to ‘She said, “… ‘ instead of ‘She said snidely, “…’ or ‘She said fulsomely,”…” is one such. If Hemingway felt the need to elaborate on the tone of what was stated, he would add a short description of what the character was doing.

One interesting aspect of Hemingway’s dialogue is his occasional use of dialogue that switches order. Usually readers expect different lines and especially paragraphs to change the attribution of who is saying what. Sometimes he would give two consecutive separate lines spoken by the same character to change the rhythm and maybe, keep the reader alert.

Wilson counsels that, like Hemingway, one good way to begin a story is to identify a character in conflict with another person, against nature, against society, or against him or herself.

And Wilson says that Hemingway adapted a pattern of story structure common to Renaissance drama, the five-act play. Wilson quotes Gustav Freytag’s study of this structure which consists of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and revelation/catastrophe.

Exposition orients the reader in the world of the story and establishes basics such as the setting and conflict.

Rising action should “heighten character conflict sprung from the activating incident.”

The climax, as Wilson describes it, is the cauldron of dramatic pressure, when events reach their peak of tension.

Falling action “emphasizes the forces that a character has turned against, building suspense about the charcter’s fate and the wisdom of the turning point.”

Either resolution, or in the case of tragedy, catastrophe settles all the dramatic tensions.

There is more to this book on Hemingway’s writing than I have outlined here of course. Whether you really like Hemingway’s writing or not, there is enough here on the craft and art of writing to make Wilson’s book worth your while.

[Home]

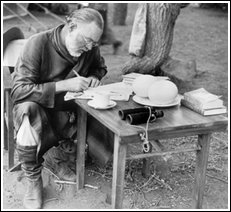

Where the images came from, from top down:

1) http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americannovel/timeline/hemingway.html

2) http://wolcottwheeler2.blogspot.com/2007/03/existential-emptiness-of-ernest.html

3) http://markmulvey.posterous.com/archive/12/2010

Additional notes:

Hemingway, of course, committed suicide in 1961 at the age of almost 62. He didn’t leave a note, but all the biographers comment he was drinking heavily, as he had most of his life. His body was giving out and he was prone to depression and paranoia. There is evidence of genetic predisposition to suicide in his family.

One has to imagine his amusement, or probably a dour lack of it, at the International Imitation Hemingway Competition, held each year in Century City, California. It has resulted in two anthologies: The Best of Bad Hemingway, Volumes 1 and II.

Hemingway did observe this about parodies: “The step up from writing parodies is writing on the wall above the urinal.”

Explore posts in the same categories: Art, Book Review, Culture, Writing

Leave a comment